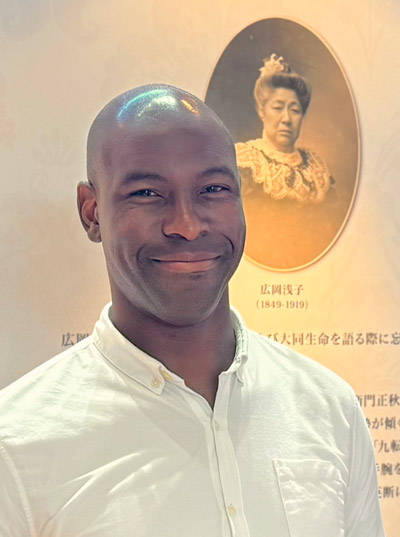

“The Origins of Daido Life Insurance” Kajimaya to Hirooka Asako

Written by Garrett L. Washington

Associate Professor

Department of History

University of Massachusetts Amherst

Established in 1902, Daido Life Insurance was in fact literally built on the foundations of its predecessor, Kajimaya. Kajimaya was one of Osaka’s leading merchant houses during the Edo period (1603-1868). It began in 1625 under family head Hirooka Kyūemon Tomimasa (1603-1680) as a rice polishing company, making refined white rice for brewing sake and for comsumption by Japan’s wealthiest families. However, the company’s operations expanded significantly as Osaka grew and prospered under the protection of the Tokugawa shogunate, becoming the commercial capital of the country. Kajimaya developed a thriving rice wholesale business that earned it a place among the most prominent merchant houses in Osaka such as Yodoya and Konoike.

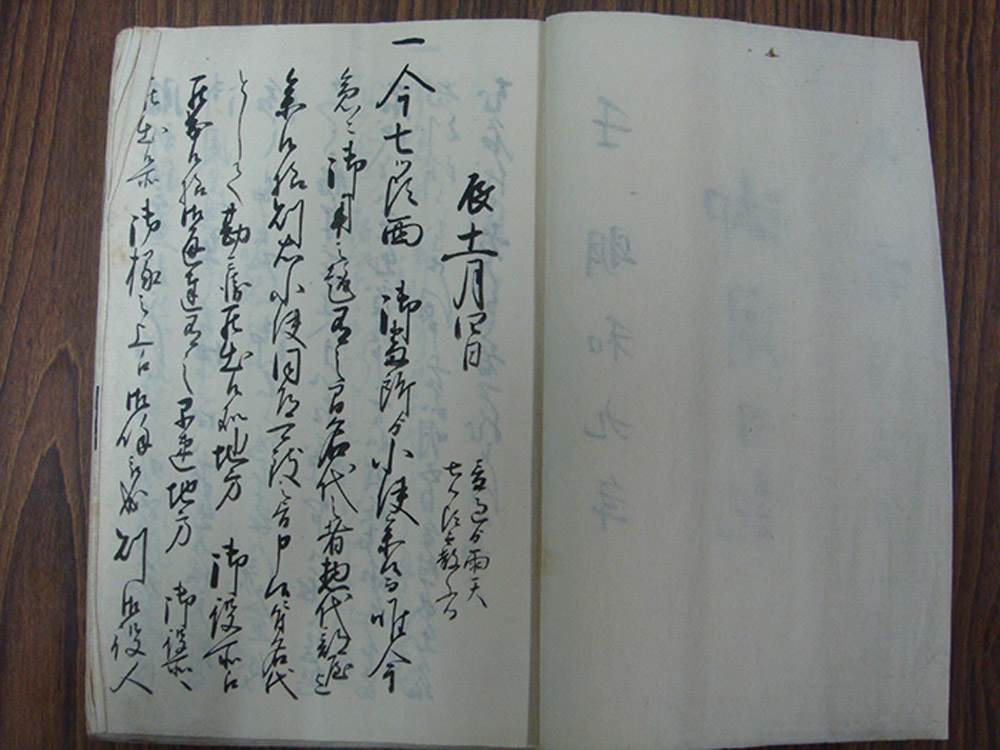

Goyo Nikki (Work Journal)

(“In 1772, a record of when Kajimaya was summoned by the Tokugawa shogunate to receive orders for monetary expenditures and financial consultation.”)

In addition to buying and selling rice to various retailers, the firm bought and sold rice futures (contracts purchasing and selling rice ahead of time at predetermined prices). Kajimaya leaders bought, sold, and traded rice futures in Kitahama at the Yodoya Rice Market, the first futures market in the world. But following the collapse of the Yodoya merchant house, Kajimaya’s role in that market changed dramatically. The market was relocated to Dōjima, directly across the river from Kajimaya’s headquarters, and given official shogunal approval to operate in 1730. And Kajimaya Kyūemon Yoshinobu (1689-1765), the fourth-generation head of that merchant house, became the first director (kometoshiyori) of the newly named Dōjima Rice Exchange. This entailed maintaining order, managing transactions, overseeing brokers and broker memberships, as well as negotiating with the city magistrate and conveying government directives to the market. The remarkable development of the Dōjima Rice Market influenced other markets across the country, and the market’s rice prices were swiftly relayed nationwide through flag signals.

Dōjima Kome Akinai by Ando Hiroshige

(Dōjima Rice Exchange image)

The financial problems of Japan’s daimyō, the lords of Tokugawa-era Japan’s approximately 260 domains or han, presented merchant houses like Kajimaya with new business opportunities. The Shogunate granted daimyō domains and their corresponding yields of rice, the main unit of currency (koku) at the time. With it, they paid their retainers’ stipends, managed domanial affairs, made biennial trips from their domains to the capital in Edo, and maintained official residences in both Edo and their home domains, in addition to living lifestyles befitting their status and rank. However, the daimyo’s year-round expenses systematically surpassed the income from rice, a seasonal crop harvested only once a year, and they accrued considerable debt. Daimyō therefore turned to firms like Kajimaya for loans. While Kajimaya was also involved in the money exchange business, converting rice and different forms of currency into gold and silver, daimyō loans (daimyōgashi) constituted the primary commerce of the merchant house. At least a solid one third of Japan’s daimyo borrowed from Kajimaya, solidifying its status as one of Japan’s most prominent daimyo lenders.

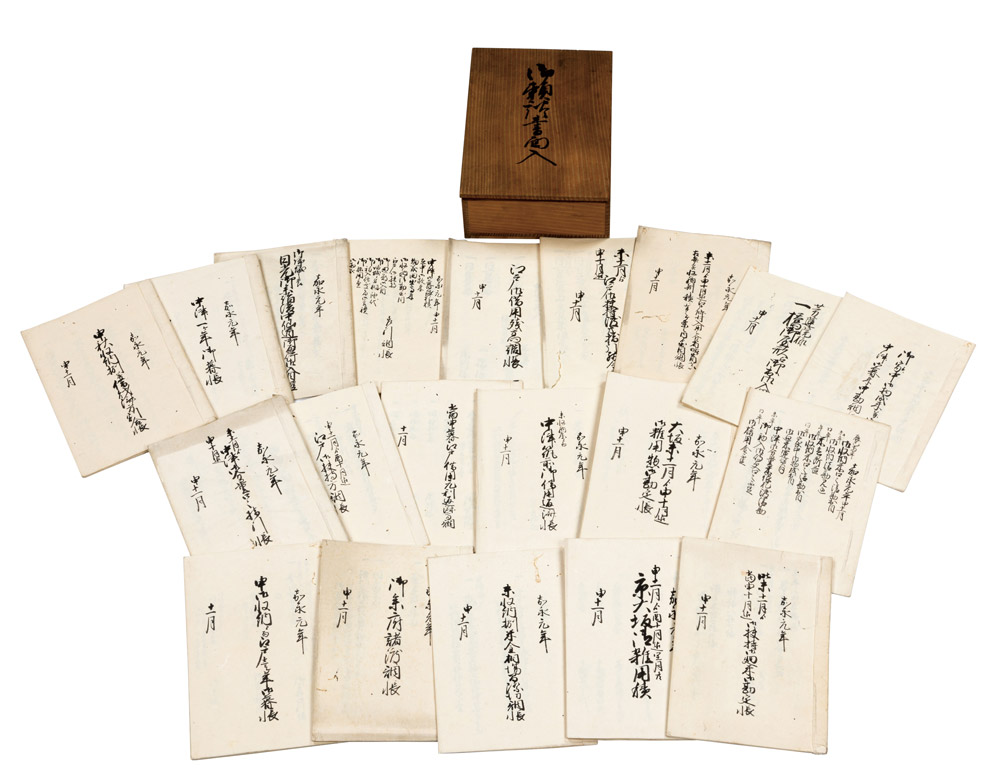

daimyōgashi image

(A record of the loan negotiations conducted between the Nakatsu Domain and Kajimaya over the course of the year 1848.)

However, the violence and upheaval of the Meiji Restoration severely damaged these foundations, threatening to bring the company’s long history to an end. Chōshū domain, whose main lender was Kajimaya, rebelled twice against the Tokugawa shogunate. The government responded by scrutinizing the firm’s accounting, unleashing on them its fearsome special militia, the Shinsengumi, and burning the company’s Osaka warehouses. But after the revolution and the ascension to power of the new Meiji government, which included many high-ranking officials from Chōshū domain, Kajimaya’s troubles only persisted. After abolishing the entire daimyo system in 1871, Meiji leaders refused to recognize outstanding loans that daimyō owed to merchant houses like Kajimaya. Complicating matters for the firm was the death of eighth-generation head of the Hirooka family, Hirooka Masa-atsu (b. 1801) in 1869 and his replacement by his son, the relatively inexperienced 26-year-old Hirooka Masaaki (1844-1909). Reeling from these developments and the devastating national economic crisis brought on by the influx of Westerners and underpriced Western goods after the end of Japan’s long period of selective isolation, Kajimaya was beset by severe financial difficulties in the 1860s.

Kinmon incident image

(前川五嶺[原画]ほか『甲子兵燹図:2巻』上巻,田中治兵衛,明治26. 国立国会図書館デジタルコレクション https://dl.ndl.go.jp/pid/3437920(参照 2025-02-28))

During this turbulent time, however, the next generation of leaders in the Hirooka family also laid the foundations for Kajimaya’s survival and future prosperity. Hirooka Kyūemon Masaaki (1844-1909), his older brother, branch family head Hirooka Goheimon Shingorō (1841-1904), and Shingorō’s wife, Hirooka Asako (1849-1919), guided Kajimaya together at the dawn of the Meiji period. Although Asako, like other merchant wives, was under the legal and economic authority of her husband, he and Masaaki recognized her abilities and worked closely with her to ran the family’s businesses. Under their collaborative leadership, Kajimaya played a central role in developing the new Osaka Stock Exchange (1878) and Uruno Coal Mine (1884), creating Kajima Bank (1888), and founding Amagasaki Spinning Company (1889) and Daido Life Insurance Company (1902). These undertakings breathed new life into the struggling Kajimaya and the fortunes of the Hirooka family whose legacy continues in not only Daido Life but also major corporations such as the general trading company Sojitz and manufacturing company Unitika.

Hirooka Asako (1849-1919)

At a time when married women were all but invisible in the business world, Hirooka Asako played visible, managerial roles in these endeavors and many others. She married into the Hirooka family in 1865 from the main house of the Mitsui family, the country’s leading merchant family. With support from the Mitsui family which had successfully modernized ahead of other merchant families, she took an active, leading role in her new marital family’s businesses. She restructured family debts, solid assets such as land and artwork, and created new business ventures to replace the Kajimaya business model that had collapsed due to the Meiji Restoration. For instance, Asako was the main catalyst behind Kajimaya’s venture into the coal mining industry. She even relocated to the heart of coal production in Japan, Kyūshū’s coal-rich Chikuhō region, to directly manage the floundering Uruno Mine in the late 1880s. Through persistence, strategic investment and borrowing, hands-on management, contract negotiations, and networking Asako turned projects like the mine into commercial successes and became one of Japan’s most successful entrepreneurs.

While she remained deeply involved in business, Hirooka Asako increasingly turned her attention to social reform. From the late 1890s, this interest led her to associate frequently with progressive Christian thinkers and activists who, like her, aimed to improve Japanese society. Asako, who as a child had been denied access to formal education in the Mitsui family because of her gender, enthusiastically supported projects to empower and educate women. She became the primary benefactor for Christian educator Naruse Jinzō’s (1858-1919) project to create Japan Women’s University (1902), Japan’s first college for women. Then, through organizations like the Young Women’s Christian Association and Women’s Christian Temperance Union, Asako rose to national prominence as an activist for women’s civil rights. However, her interest in social reform extended beyond the women’s movement. She established and funded a night school at the turn of the century for employees to study business and commercial law at Kajimaya’s various branches.

While these initiatives were closely connected to movements for social change related to her relationship with Protestant Christianity-a religion to which she converted in 1910-they also aligned with Kajimaya’s history of contributing to society. During the Edo period, this merchant house provided funds and food in the aftermath of natural catastrophes such as tsunami, earthquakes, crop failures, and famines. Furthermore, Kajimaya supported Buddhist education through frequent, substantial donations of funds and land to the institution that later became Ryūgoku University. Since its establishment in 1902 Daido Life has emphasized the goal of serving society, carrying on these longstanding traditions and embodying the ideals of its cofounder Hirooka Asako. The site of the current Daido Life headquarters in Osaka is where the Kajimaya store was established 400 years ago. It represents Osaka’s long-standing development as an economic hub and stands as a reminder of the important place of Kajimaya and its successor Daido Life in Japan’s financial history.